Giotto di Bondone

Giotto di Bondone was a painter, sculptor and architect whose work singlehandely initiated the Rennaisance. Working from around 1290 to the year of his death in 1337, Giotto sharply departed from the Byzantine way of depicting Christ and other religious figures in favor of the more lifelike, naturalistic style that he ordained. Not to put down the Byzantines—to the modern eyes, their elongated forms and stylized features are stylistic forerunners of illustration and cartoon. But in Giotto’s hands, Jesus, the Apostles, Mother Mary and Mary Magdalen became real human beings who had weight and form, wore real clothes and expressed human emotions, instead of the remote, otherworldly figures that had characterized religious art for hundreds of years.

Giotto is also one of the first European artists to use a system for determining linear perspective in his work, purportedly using an algebraic formula to lay out his paintings.

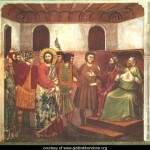

One of the earliest examples is “Jesus before the Caif,” which portrays the biblical scene of Caiaphas tearing his robe upon hearing Jesus’ blasphemy, a painting rich in color and drama.

In 1305, while Giotto was working on another masterpiece, the Scrovegni Chapel fresco, Dante Alighieri stopped by. Giotto was already famous by this time and Dante wanted to meet the great artist who continued to paint while they visited, with Giotto’s children playing underneath the artist’s scaffolding. As they spoke, Dante couldn’t help noting to himself how homely Giotto’s children were. No longer able to restrain himself, Dante finally asked the artist, “How can a man who paints such beautiful pictures create such—plain children?” To which Giotto replied, “It’s my own fault—I made them in the dark.”

Just then a ragged old woman who cleaned the chapel came bumping by with a broom. Pushing a strand of filthy hair out of her face, she stopped and stared at the finished portion of the panel Giotto had been working on, The Last Judgement, where the figure of Satan sat in Hell, swollen huge from the lost souls he was shoveling into his maw like so many chocolates.

The broom clattered to the floor as the woman crossed herself, a look of horror spreading over her face. “Oh, my Lord! That’s, that’s—it’s a monstrosity to show such things! It’s—he’s—too real! Oh, my Lord!” She pointed at Giotto, who stared back in mute surprise. “You! You horrible thing! You’ve conjured up the Devil by doing this—Oh! I shouldn’t say his name! He’s already here!!”

The broom clattered to the floor as the woman crossed herself, a look of horror spreading over her face. “Oh, my Lord! That’s, that’s—it’s a monstrosity to show such things! It’s—he’s—too real! Oh, my Lord!” She pointed at Giotto, who stared back in mute surprise. “You! You horrible thing! You’ve conjured up the Devil by doing this—Oh! I shouldn’t say his name! He’s already here!!”

As the old woman turned and ran from the chapel, the two men collapsed in laughter.

But later that day as Dante returned home, he no longer felt like laughing. The look of horror on the old woman’s face haunted him as he traveled along, and he began to wonder if maybe she’d been right. Were Giotto’s skills too good? Had his considerable abilities been acquired through some unholy bargain? How else could he so accurately illustrate what men had only seen in nightmares?

Some years later, when Dante was writing his Divine Comedy, he knew Giotto would have a place in it somewhere, but exactly where was a question with which he’d wrestled for months. In the end he had to flip a coin to decide whether or not to place Giotto in the company of other artists and saints in one of the highest rings of heaven, or consign him to one of the lowest circles of hell where souls were tormented for all time.

Source information on Byzantine Art, Giotto & Dante story: Wikipedia

Fictionalized by Joe Henderson

Really liked what you had to say in your post, Giotto di Bondone | idahoorange.com, thanks for the good read!

— Gino

http://www.terrazoa.com

Thank you, Gino, glad you liked it.

–I.O.

I visited a lot of website but I think this one holds something special in it in it

I believe other website proprietors should take this internet site as an model, very clean and good user friendly design and style .

Thanks.

844132 534331Attractive part of content material. I just stumbled upon your web site and in accession capital to claim that I acquire in fact enjoyed account your weblog posts. Any way I?ll be subscribing to your feeds and even I achievement you get entry to constantly swiftly. 769252

Thanks.

I’ll right away snatch your rss as I can not find your e-mail subscription hyperlink or e-newsletter service. Do you have any? Please let me realize in order that I may subscribe. Thanks.

Sorry it took so long to get back to you. Thank you for kind words, am working on subscription.